Amiens Cathedral in Brief

Built between 1220 and 1270, and designed by the architect so-called Robert de Luzarches, Amiens Cathedral, or Cathédrale Notre Dame d’Amiens, which means The Cathedral of Our Lady of Amiens, is a Roman Catholic Cathedral and seat of the Bishop of Amiens. Along with the cathedrals of Chartres and Reims, Amiens Cathedral is a member of the illustrious triad of High Gothic or Classical French cathedrals of the 13th century. It is the tallest and largest complete cathedral in France, thanks to its stone-vaulted nave reaching a height of approximately 42 meters, and its greater interior volume.

Furthermore, Amiens Cathedral is renowned for the quality and the quantity of early 13th century Gothic sculpture in the main façade and the south transept portal, and a large quantity of polychrome sculpture from later periods inside the building. In 1981, UNESCO designated this cathedral a World Heritage Site, citing “the coherence of its plan, the beauty of its three tier interior elevation, and the particularly fine display of sculptures on the principal façade and in the south transept”.

Understanding The High Gothic Period in France

According to Wilson, the term “High Gothic” as used in English writing on medieval architecture embodies a construct of at best doubtful merit. The adjective “high” is a part of a value judgment which places the very different cathedrals of Chartres, Reims, Amiens and Bourges at the peak of French Gothic, and which sees the greater homogeneity of the Rayonnant phase as a symptom of decline. Thus, High Gothic is acclaimed as an architecture of individuality and pioneering vigour.

Moreover, in the book The Gothic Cathedral, the author states that the four aforementioned cathedrals present better than any other 13th century French church a coherent and comprehensive image of the Gothic Cathedral, for they were carried out more or less in accordance with their original architects’ intentions, and they received a full complement of sculpture and stained glass. They also make a good story since together they form an exceptionally clear and satisfying developmental sequence.

The Emergence of Great Paris Basin Cathedrals

In his book “A Guide to Understanding The Medieval Cathedral”, Scott states that The Great Paris Basin proved fertile ground for Gothic Cathedral for good reason. Unlike other regions of France, such as Flanders, Champagne and Burgundy, where powerful counts supported the construction of the monasteries and cathedrals, the vicinity of Paris had seen precious little church-building during the previous century because of the general weakness and financial impoverishment of the monarch.

But once the monarch began to gain strength, the absence of a recent regional style, combined with the fact that most abbeys and cathedrals in the Great Paris Basin were old and in disrepair, created an opportunity for wholesale renewal of churches that could not have arisen elsewhere.

The Significance of Cathedrals In A Grandeur Manner

According to Scott, as the cathedral is the seat of the bishop, who is charged with the care of souls within a designated area, the bishops compared what they had built or planned to build with what other bishops had done or planned to do. It became a sign of one’s place in the church and society to claim that the height of the nave of one’s cathedral, the magnificence of its tower or spire, the grandeur and beauty of its stained glass, the length of its nave, its overall mass, whatever, was greater, bigger, better, more audacious than any that preceded it.

Indeed, as a practical manner, it would have been impossible to raise the money needed to undertake building a new cathedral unless it was to be more impressive than any already planned, under construction, or completed. This situation can be called as “a great cultural competition”. To call this competition a mere status contest diminishes its true nature. Gothic cathedrals and great monastic churches were vital elements in the larger social project of managing the relations between the society and the sacred.

In his book “The Gothic Enterprise: A Guide to Understanding The Medieval Cathedral”, the author also states that in cathedrals and other kinds of great churches being built in France during this period, the quest was to achieve ever greater interior height.

|

| A few of the Gothic cathedrals in the Great Paris Basin. |

The History of Amiens Cathedral

Early Christianity Period in Amiens

The town of Amiens has a long and turbulent history. The first mention of what is now Amiens, France came from the writings of Julius Caesar, in “The Gallic Wars and Other Commentaries”. He mentioned the people, the “Ambiani”, as well as the town, “Samarobriva”. For over a millennia, the town of Amiens has stood the test of time, through periods of peace, revolutions, and wars. Churches have become an integral part of the landscape of Amiens; according to local legend, the first church was founded in the 3rd century by St. Firmin. After his martydom, he was succeeded by another man named Firmin, known as St. Firmin the Confessor. Nothing is reliably knowns regarding these Firmins because their biographies were invented in the Middle Ages.

But even if one relies on historical evidence, Amiens is still an ancient foundation. It was in this city in 334 that St. Martin of Tours was baptized and famously shared his cloak with a beggar, and the first Bishop of Amiens is recorded in 346. The first Christian community was short-lived, however. It was wiped out by pagan barbarians who swept through Northern France in 407. Amiens was re-evangelized beginning in the late 400s under the direction of St. Remi, Bishop of Reims, and became more intense after the conversion of Clovis to Christianity in 498. The first known bishop in this period is Ebidus, whose presence is recorded at a council of 511.

According to Henderson, the first churches that are recorded probably date to the 5th century. Within a parallel twin church complex, the northern church was dedicated at first to Saints Peter and Paul, later to St. Firmin The Confessor, whose relics were housed there. The southern church was dedicated to the Virgin Mary and St. Firmin The Martyr. It was used by the bishop, and, over time, the name of the building was changed to Notre Dame.

The Romanesque Period in Amiens

After a fire destroyed much of the city, construction on a Romanesque cathedral began in 1137. Consecrated in 1152, this building hosted the wedding of King Philip II of France and Princess Ingeborg of Denmark in 1193. During this period, Amiens Cathedral attracted a respectable number of local pilgrims due to its relics of local saints, such as Fuscien, Victoric and Gentien.

In 1206, Amiens became one of the most important pilgrimage destinations in Europe when supposed skull of St. John The Baptist was brought back from Constantinople by Crusaders. The impressive relic would be the principal source of revenue for the cathedral for years to come. The Romanesque church soon proved too small to accommodate such an influx of pilgrims, enabling the construction of the grand Gothic cathedral that endures today.

The Gothic Period in Amiens

In 1218, when the cathedral was destroyed by a lighting strike to the roof, the bishop of the time, évrard de Fouilloy seized the opportunity to build a new cathedral, one much greater than its predecessor, in the Gothic style, which was the fashion at the time. The ambitious bishop wanted to build a building unequalled by all other cathedrals of Christendom. The new statuary was to be a Bible in stone that would teach the Christian people Bible stories. The great collection of statues at Amiens would later be known as “The Bible of Amiens”. The bishop charged the architect Robert de Luzarches with the duty of building the cathedral and construction began in 1220.

The rapid progress made on the cathedral was possible due to the prosperity in Amiens. In fact, under the reign of Philippe-Auguste, the town enjoyed a virtual monopoly of the woad trade. Cultivated in the region, the plant was used in dying woollen fabric and built the fortunes of Amiens’ middle class. Amiens’ location also contributed to the fortune of diocese, being between Flanders, where the textile industry was flourishing, and the famous fairs of Champagne.

The deaths in 1222 of Robert de Luzarches and Bishop Evrard de Fouilloy did not slow construction of the cathedral; in fact, the opposite was true. Under the impulse of the new Bishop Geoffroy d’Eu and the architect Thomas de Cormont, donations continued to fund the great work. In 1228, the walls of the nave had already reached the point at which the vaults would begin and in 1230, the nave was entirely finished.

Around 1236, the façade had reached the height of the cornices above the rose window, and the base of the transept had been completed. Succeeding from Geoffroy d’Eu, the new Bishop Arnoult oversaw the creation of the choir and the construction of the apse chapels. After the lack of budget and other undesirable conditions, work started again and continued at a good pace until 1269, the year that the choir was completed.

By 1288, the lion’s share of the cathedral’s structure had been completed, with Bishop Guillaume de Mâcon overseeing the completion of the work on the transept spire. That same year, the master-builder Renault de Cormont created the labyrinth of the nave. Thanks to the short period of construction (1220-1288) of Amiens Cathedral, this Gothic work displays a consistent and harmonic architectural style that is rarely seen in the other French cathedrals.

The towers of the façade were unfortunately not as high as those at Reims or Chartres due to the lack of funds. The south tower was completed in 1366, the northern tower, however, produced some challanges. In 1375, a buttress had to be constructed to support the tower because of the slope on which it was built. The opportunity was taken to elaborately decorate the buttress in Flamboyant Gothic Style. It was only in 1402 that the peak of the north tower was finally completed.

The Destruction and Restoration in Amiens

Amiens Cathedral almost collapsed in the 16th century. In 1498, the master-builder Pierre Tarisel noticed that the building was about to collapse and so began to work on strengthening the flying buttresses of the nave and transept. Tarisel found that tha large pillars of the transept crossing were dangerously unstable under the thrust of the great archways which were 42 meter height. He had a genius idea; he surrounded almost all the building with an iron wall tie, along the triforium of the nave and transepts. This wall tie, still here today, was put up in less than a year. It made the cathedral stronger and so protected it for the centuries to come.

Like many other European cathedrals, Amiens Cathedral suffered damage from various wars and disasters in subsequent centuries, including Huguenot Iconoclasm in 1561, hurricanes of 1627 and 1705, and even the explosion of a nearby powder mill in 1675. Much of the medieval stained glass was lost during these calamities.

The Cathedral has suffered little in the troubled period of the French Revolution. Damages were limited to few destroyed fleurs de lys (royal amblem), crosses and statues. The exceptional statuary of the cathedral’s great portals thus remained intact. At the time, the sanctuary was transformed into a Temple of Reason and Truth. The statue of St. Genevieve converted in the Goddess of Reason is a testament of this.

In the 19th century, the Cathedral benefited from the fashion days of Gothic art in Europe due to intellectuals such as Victor Hugo, the author of the novel of “Notre Dame de Paris”. The pooe state of Amiens Cathedral was of concern for the architect Eugéne Viollet-le-Duc, who carried out the restoration of the building over 25 years. The renovation work was sometimes controversial, notably by the addition of completely new components which never existed in the Middle Ages. At the top pf the great façade, Viollet-le-Duc added a gallery known as “Galerie des Sonneurs”. The aim of the gallery was to link the two towers as a matter of aesthetics.

During both world wars, extensive measures were taken to project Amiens Cathedral: the stained glass windows were carefully removed and sandbags were stacked high in the nave. Fortunately, the cathedral remained untouched during both wars, yet did not entirely escape destruction. Among the windows lost in this disaster were two of the cathedral’s oldest windows ffrom the apse; one depicitng the Tree of the Jesse and the other the Acts of the Apostles.

UNESCO designated Amiens Cathedral a World Heritage Site in 1981, citing “the coherence of its plan, the beauty of its three-tier interior elevation and the particularly fine display of sculptures on the principal façade and in the south transept.

In 2000, the three great portals of the west façade were cleaned with an expensive but very effective method called ”photonic disencrustation”, which used lasers to remove centuries of dirt and grime from the stone. Revelaed underneath were traces of the original polychrome paint that decorated the sculptures, a rare and remarkable survival.

The Plan of Amiens Cathedral

|

| Ground Floor Plan of Amiens Cathedral. |

In his book about Amiens Cathedral, Murray provides an illustration of the way geometry enables us to derive the basic overall design of Gothic great churches. He says, “the design begins with the square of the crossing. Peripheral spaces will be, in a sense, unfolded from the central square”. He shows how each dimension of the nave, choir and double aisles of Amiens can be drawn by rotating diagonal lines from the central crossing.

He also notes that “the designer is obviously also concerned with allowing numbers to express proportions, hence, the repetition of 3’s and 5’s; 5’s and 7’s. A similar proportionality has been found repeatedly in other Gothic cathedrals and great monastic churches, including ones built well before the Gothic style appeared. Clearly, regular proportions and modular arrangements of repeated volumes were important to medieval architects.

|

| How the plan of Amiens Cathedral "unfolds" from the center. |

The Exterior of Amiens Cathedral

West Façade

Begun in 1220 by the architect Robert Luzarches, the façade of Amiens Cathedral is dominated by two towers. The buttresses run down to the level of the portals, dividing the surface into three vertical bays, which correspond to the three aisles of the nave that lie behind it. The bays are intersected and tied together by two horizontal galleries and by the zigzag of the gables. The height of the side aisles is marked by the arches above and behind the gables, not very clearly or organically, it must be admitted, but the peak of the main vaults is filled by the great “eye”, the rose window.

To either side of the rose are pairs of arches, and only above this level were the towers originally meant to rise free and unimpeded. The regular vertical and horizontal divisions are from the so-called harmonic façade that is typical of French Gothic design.

The west façade of Amiens Cathedral, from bottom to top, consists of three portals, including the great central portal or The Portal of the Last Judgment, the right (south) portal or The Portal of Mother of God, the left (north) portal or The Portal of St. Firmin; the triforium formed by a series of twin arcades; The Gallery of Kings; Rose Window redesigned in the 16th cent. in Flamboyant Gothic Style; Galerie des Sonneurs added by Viollet-le-Duc in 19th cent.; the north and south towers.

|

| The west façade of Amiens Cathedral. |

The Critics Regarding The West Façade

In his book “The Gothic Architecture”, Branner criticizes the west façade in a positive and descriptive manner: “The façade of Amiens is covered with decorative sculpture-blind arcade, pinnacles with crockets, and cusps. The portals contain a more elaborate iconographical program, however, for in one sense they were considered the gates to Paradise, and in another they formed the area where doctrines of the Church could best be displayed to the people.

Each portal is dedicated to a specific theme, the central one to the Last Judgment, the one on the right to the Virgin and the one on the left to Siant Firmin. These last two themes are repeated on the transept portals, St. Firmin to the north and the Virgin to the south. On the west façade, each tympanum is embedded in an array of sculpted archivolts, which represent angels, clerics, and subjects from the Bible. Each archivolt in turn surmounts the statue of a saint, angel, or prophet, beneath which are found reliefs of the Virtues of Vices, the Signs of the Zodiac, and the Labors of the Months.

The themes are interrelated vertically, horizontally, and sometimes across the portal, from one side to the other. Thus, the façade of Amiens serves both as a monumental frontispiece for the Cathedral and as a bearer of a complex statement of theological doctrine. Most of all, the portals are wide and welcoming gates which draw the observer through the façade and into the building behind them. As we pass through them, we see the whole length of the monument laid out before us, the nave, the crossing and the chevet, which terminates in the hemicycle.”

On the contrary, Wilson criticizes this façade in a negative sense: “The extremely tall proportitioning of the main vessel resulted in a huge gap between the rose and the central portal, which the architect filled with a gallery of kings and a triforium. Skied above this plethora of arches, the rose looks insignificant. No less unhappy is the squatness of the aisle windows and the way they lurk behind the huge side portals. The arches of the portals have become disproportionately tall compared to the jambs and the pinnacles between the gables appear ludicrously big in relation to the gables and to the buttresses of which they form part. In surface decoration as well as width these major vertical elements extraordinarily inconsequential.

Almost the only commendable feature of Amiens façade is that when viewed frontally, it conceals its worst defect, namely that the towers are shallow rectangular affairs standing not on the western aisle bays but on the hind parts of the truly cavernous portals. The bizarre arrangement was probably a device to overcome the problem of restricted length caused by the presence of earlier buildings which could not be demolished; to have set towers over the west aisle bays would have given the nave very stunted external proportions, for its untowered part would have been barely as long as the main vessels of the choir.”

The West Façade Portals

|

| The western frontispiece of Amiens Cathedral displays a program of three sculpted portals. |

The central portal is eschatological, showing a scene of the Last Judgment. The lowest register of the lintel shows, in the center, Michael weighing souls. The left side of the balance holds a lamb, the right a demon’s head. A demon below the right side interferes with the scale. To the left an right, the dead rise from their tombs, flanked by trumpeting angel. The lintel is framed on top and bottom by a foliate band.

The second register shows saved souls on the left being ushered into Heaven, while on the right damned souls are being thrown into the Hellmouth. Above the saved souls are angels bearing crowns. Above the damned souls are angels wielding flaming swords.

On the tympanum, Christ sits in judgment below an architectural canopy. The Virgin Mary kneels to his left, and John the Evangelist to his right. Flanking them are angels carrying the instruments of the passion. Above the canopy, two angels cary representations of the sun and moon, and in the center is the image of Christ at the Second Coming, with two swords issuing from his mouth and a scroll in either hand.

|

| The Last Judgment Scene mentioned above. |

There are eight bands of voussoirs. The lowest register of each band shows, on the left, angels with saved souls, and on the right, damned souls tortured by demons, some on horseback. The first band shows angels with hands folded in prayer. The second band shows angels with saved souls in their arms. Then come martyrs, confessors, virgins, apocalyptic elders, a Tree of Jesse and patriarchs of the Old Testament.

|

| The trumeau figure and the voissoirs. |

The trumeau figure on the central portal is a figure of Christ known as the Neau Dieu, seen trampling the lion and the serpent. Either David or Solomon is depicted on the aedicule below the trumeau. The doorframe to the left of the portal depicts the Wise Virgins, and the frame to the right depicts the Foolish Virgins.The embrasures below depict, on the lower register, the Vices, and on the upper register the Virtues.

|

| The Portal of Mother of God (South Portal) |

The south portal addresses the theme of the Virgin Mary as Mother of God. The lowest register of the lintel depicts six Old Testament patriarchs flanking the trumeau canopy, which contains a representation of the Ark of the Covenant. Only Moses, who carries the tablets of the law to the left of the canopy, and Aaron, who carries a flowering rod and wears a diadem to the right of the canopy, are identified.

The next register shows the Virgin Mary's Dormition on the left, and her Assumption on the right. The tympanum depicts the Coronation of the Virgin. She is seated to Christ's left, and angels place a crown on her head from above. Christ and the Virgin are flanked by angels carrying tapers and censers. This portal contains three bands of voussoirs. The inner band depicts angels carrying liturgical instruments. The outer two bands depict the kings of the Tree of Jesse.

The trumeau figure is of the Virgin Mary carrying the Christ Child. The jamb figures, beginning on the left exterior, are identified as the Queen of Sheba, King Solomon, Herod, and the Three Magi. On the right side of the portal, beginning with the interior, are shown the Annunciation, with the Angel Gabriel and Mary each occupying their own column, followed by the Visitation, with Mary and St. Elizabeth on their own columns, and finally the Presentation in the Temple, with Mary with the Christ Child and Simeon on their proper columns.

Below the column figures, the quatrefoil embrasures depict, on the left side from exterior to interior Sheba and Solomon, the Massacre of the Innocents, and the Journey of the Three Magi, while on the right, from interior to exterior, are shown the stories of Gideon's fleece, the burning bush, Aaron's flowering rod, the history of Zacharias and Elizabeth, and idols falling from their stands during the Flight to Egypt.

|

| The Trumeau figure of the Virgin Mary (South Portal). |

The north portal explores the theme of St. Firmin and other local saints. The lowest register of the lintel depicts six seated bishops, three on each side of the trumeau canopy, which resembles a reliquary chasse. Two of the figures hold croziers, representing the bishop's duties as priest. Two hold books, representing their role as teachers, and two hold staffs, representing their role as administrators.

The next register depicts the invention of the relics of St. Firmin, first bishop of Amiens, by St. Salve, bishop of Amiens in the sixth century. He is flanked on either side by representations of the people of the four neighboring towns who were drawn to witness the invention by the sweet odor of the remains.

In the tympanum, the chasse containing the remains of St. Firmin is being carried to the church by monks. They are escorted by monks and altar boys carrying liturgical instruments, and are eagerly awaited by a crowd of people who peer from architectural frames and climb verdant trees to get a better view.

|

| The Portal of Saint Firmin (North Portal). |

There are three bands of voussoirs. The inner band depicts angels holding crowns, with a seated figure of a bishop at the base of each side and a figure of Christ crowned at the center. The second band depicts angels holding tapers, with a head of God the Father at the center. The outer band depicts angels swinging censers. The trumeau figure on the north portal is that of St. Firmin in bishop's garb. The jamb figures are, on the left side from exterior to interior St. Ulphe, an angel with scroll, two cephalophores, another angel with censer, and a bishop.

The right jambs depict, from interior to exterior, a bishop (possibly St. Firmin the Confessor, a bishop who erected a church on the site of St. Firmin the Martyr's tomb), a deacon, another bishop (possibly St. Salve, the bishop who discovered St. Firmin's relics), and three saints. The embrasures below show the labors of the month on the lower register and the signs of the zodiac on the upper register.

|

| The Trumeau figure of the Portal of St. Firmin |

The Triforium and The Gallery of The Kings

On top of the three portals is the lower gallery dating from 1235, which is lavishly decorated with archways and small columns. This gallery is lined with large openings which lit the central nave of the cathedral before the great organ was installed. The lower gallery itself is surmounted by the Gallery of Kings, which is located at 30 metres above the parvis. There are 22 statues in the Gallery of Kings and it is not certain whom these statues depict. They date back to the first half of the 13th century.

The central part of the façade has eight statues 3.75 metres high. Six other statues are placed on the western side at the base of each of the arcades, while two are in the front of the central buttresses of the façade. These statues appear relatively badly proportioned with their short limbs in comparison to their big head.

|

| The Lower Gallery and the Gallery of Kings. |

The Rose Window

The rose window is situated just above the central part of the Gallery of Kings and its paved terrace. This Flamboyant Gothic style rose window dates from the 16th century and was ordered by the mayor of Amiens. It is also known as the “The Rose of the Sea”. The rose window cannot be seen in its entirety from the outside as the ledge of the terrace balustrade covers the lower part.

The South (Rayonnant Gothic) and The North (Flamboyant Gothic) Towers

The towers of Amiens Cathedral lack size and rather resemble to parts of a tower. Unlike those of the Rouen and Chartres façades, the small size of the towers at Amiens Cathedral does not contribute to the upward thrust of the building. It is the spire of the transept, more than 100 metres high and visible from afar, which fulfils this role instead.

|

| The Towers, The Rose Window and Galerie des Sonneurs. |

The Galerie des Sonneurs, Gargoyles, Chimeras and Musician Kings

The high parts of Amiens Cathedral have plentiful amounts of medieval sculptural works that are often over-the-top or frightening, such as gargoyles, chimeras and Musician Kings. There are countless gargoyles at the top parts of the cathedral. Often they are very high and are real pieces of statuary. It is important not to confuse gargoyles and chimeras.

Gargoyles were placed at the end of the gutters to drain rainwater from the roof. They go over the edge to drain the water as far as possible from the cathedral walls, so that the walls do not get damaged. With opened mouths, gargoyles often take the form of mythical animals that are frightening and fierce. Designed by many artists who were given artistic freedom, these creatures are all different and have a variety that is close to infinite.

Chimeras, in contrast to gargoyles, do not have a purely decorative function. They are simply mythical, diabolical and often grotesque statues. They often have closed mouths and are perched on mounts that elevate them. They are found in the heights of the cathedral, on balustrades or at the top of buttresses where they replace pinnacles. The chimeras have duty to watch over the city, like the famous mythical animals of Notre-Dame de Paris, added by Viollet-le-Duc.

Unlike chimeras, the statues of the Musician Kings represent very pleasant characters. The Musician Kings are dispersed over all the roofs of the cathedral. A large number of them are found just behind the towers of the western façade, around the terrace of the “Chamber of Musicians”. This terrace is situated on the roof between the Gallery of Bell Ringers and the western end of the attic of the nave. Another series of Musician Kings that are much easier to admire are at the top of the buttresses of the axial chapel, at the chevet of the cathedral just behind the choir.

At the top are the two towers which the architect Viollet-le-Duc linked together with the “Gallery of Bell Ringers” in the 19th century. This curtain-wall, covering the area between the two towers, is surmounted by a second gallery containing exquisite ornamental archways.

|

| The Tympanum of South Transept Portal |

The South Transept Portal

The south transept portal of Amiens also displays a refined sculptural program addressing the life and miracles of St. Honoré. The lowest register of the lintel depicts the twelve apostles. The next register depicts the miraculous effluence of holy oil anointing St. Honoré as bishop of Amiens to the far left. A cluster of clergy members discuss the miracle to the right.

In the center stands an altar with chalice and screen. To the right of the altar sits St. Honoré, below a canopy signifying Ecclesia, with his hand on a book. He looks up from reading to hear of the discovery of three saints, whose invention is depicted at the far right. Here, as with the invention of St. Firmin's relics, trees burst into bloom. The third register shows, to the left, St. Honoré performing mass, flanked by attendants carrying liturgical instruments. On the right, a statue of the saint sits on an altar, and a blind woman is healed by touching her eyes to the altar cloth. Behind her another figure with a cane is waiting to be healed.

The fourth register shows a procession of St. Honoré's reliquary chasse. It is carried on the shoulders of monks, and below it three people with various afflictions touch the casket, hoping for miraculous healing. On the right, a crowd gathers to witness the procession. On the tympanum, Christ is shown on the cross flanked by the Virgin Mary and John the Evangelist and two angels with censers. This refers to the miracle during which a neighboring church supposedly inclined its head towards St. Honoré's relics.

|

| The North Transept Portal. |

The Chevet, Flying Buttresses and Pinnacles

The east end is a magnificent sight, resembling a giant medieval reliquary with its pinnacles and pyramids. The chevet with seven radiating chapels and was used as a model for many other churches. In his book, Branner claims that on the exterior, the radiating chapels come into their own. Elsewhere the plan of the Cathedral is rectilinear, but here, on the great curve of the chevet, the sharp faces of the polygonal chapels undulate in and out, pushing outward between the buttresses and echoing at a smaller scale the dominating shape of the hemicycle.

The exterior of Amiens Cathedral is not a simple envelope that seems to transform the volumes into a solid mass, however. It is rather a half-open, half-closed composition of flying buttresses, pinnacles, and pyramidal roofs. If the interior volumes have finite limits, the exterior massing has no distinct beginning or end. The chevet is similar to the transept and to the nave in this respect, but it is only the flat terminals, with their portals, that provides access to the interior. The towers on the west façade, rising above the body of the church, indicate that the main entrance to the Cathedral will be found directly below.

|

| The North Nave Flying Buttresses From Roof Level. |

The Interior of Amiens Cathedral

The plan of Amiens Cathedral is very typical of the Classical Gothic buildings in France. The transept is pulled down the body of the nave, instead of copying earlier models that have a transept more towards the east end of the building. The transept is not the focal point of this church, but instead is very short and truncated.

The nave and the two side aisles are the center of attention, leading to the apse and ambulatory. Coming away from ambulatory there are seven radiating chapels. This plan is very similar to the plans of cathedrals of Chartres, Reims and Notre Dame de Paris.

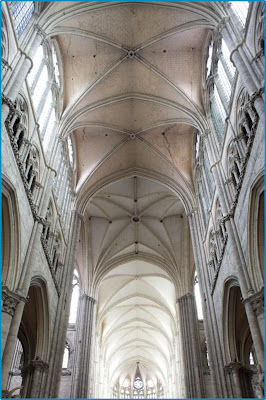

|

| The Nave From Triforium Level Looking West. |

Entering from the west façade, the eye is immediately drawn up by the massive segregated columns that rise from the floor to different destinations. The large columnar piers stop halfway up the wall and spring into tall, pointed Gothic arches. The smaller secondary columns rise al the way to the ceiling as reinforcements for the rib vaults that cross the ceiling or to create the arches for the clerestory windows.

For every column that creates a rib vault, there is also an intermediate transverse vault that crosses the entire length of the ceiling, segregating space on the Cathedral floor and creating the impression of a sturdy barrel vault underneath the Gothic rib vaults. Created of white stone, the impression is soothing and radiant. The crispness of design and organic feel of the interior is directly related to this grouping of columns.

|

| The Nave Vaults and Columns. |

Looking up the columns, the eye is drawn by the repetitive harmony of the gallery’s columns. For each two tall columns that go up to the ceiling, there are two sets of gallery columns. These are beautiful triforiums that are repeated down the length of the nave, as a way to counteract the verticality that dominates this space.

After looking up at the columns, the eye is almost forced back to the floor by an overwhelming floor design. Geometric designs in stark black and white stone draw the eye into a plethora of sharp turns and angles. There are many different designs, but the largest is the labyrinth, placed in the center aisle of the nave. The impression is one of ordered chaos, with each design competing with another of the viewer’s attention. After the shock of the dichromatic floor, the viewer’s eye is drawn again by the enormous windows of the nave and clerestory. All of the windows have mostly clear glass, with stained glass around the edges.

|

| The South Nave Elevation From Triforium Level. |

These windows flood the nave with light and give the nave an illumination that seems to reflect off the white stone and fill it with an unearthly radiance. The strong lateral pull of the nave and triforium draws the eye and body toward the apse, where the arches become smaller and narrower.

The transverse ribs are no longer used, instead this time, rib vaults from the hemicycle all come to the same point and focus the eye not on the walls, but on this point from which the eye drops from the ceiling to the altar. This gives an impression of divine immanence and presence within the cathedral.

According to Wilson, Amiens' piers are of similar thickness to those at Chartres and Reims, but their effect is far less oppressive because they are more widely spaced and also far taller in their proportions, approximately twice as high relative to their girth. The tremendous vertical impetus generated by the piers is part of a larger pattern of extreme verticality, for the main vessels here are more steeply proportioned than in any earlier church. At 42 meter the internal height of Amiens is also unprecedented.

He states at Amiens, all the equivalent shafts start from the sill of the triforium. A similarly compelling visual logic governs the high vault responds, whose constituent shafts increase in number and fineness from the floor upwards and thus partake of the character of the levels where they occur: bold single shafts on the still relatively robust piers, triple shafts between the fine-gauged roll mouldings of the arcade arches and five-shaft groups in the upper storeys, where the delicate linearity of tracery has full rein.

|

| The Triple Shafts and Piers Carrying The Vault. |

The stability of the vaults at Amiens depends partly on the use of the tas-de-charge technique. This involves substituting massive, horizontally cursed springer blocks for what one readily accepts as a series of independent and radially constructed ribs. The main advantages of making vault springings from blocks far bigger than the stones used elsewhere in the building was the strengthening of those parts of the structure most subject to lateral thrusts.

Another technical refinement related to the use of larger blocks, and which appears to have been importantly developed at Amiens, is the use of components of standardized size and shape. From its first appearance, bar tracery was largely built with systematically jointed blocks, so that equivalent components destined for windows of the same size would have been interchangeable by the setting masons putting up the stonework.

|

| The Tas-de-Charge Technique in the Rib Vaults. |

According to Scott, the quest for geometric uniformity, when followed consistently, gives Gothic cathedrals their characteristics organic unity. Every part of the building is linked logically, harmoniously, and proportionally to the whole. According to this principle, called as "progressive divisibility" by Erwin Panofsky, "supports were divided and subdivided into main piers, major shafts, minor shafts, and still more minor shafts; the tracery of windows, triforia, and blind arcades into primary, secondary, and tertiary mullions and profiles; ribs and arches into a series of moldings.

The phrase "progressive divisibility" conveys the idea of a "visual logic" in which the subordinate members of a structure are related to one another to form a coherent whole. One hallmark of the Gothic style is the manner in which this principle is expressed visually, often even in the smallest details of individual shafts and moldings. The piers, shafts, and vaulting of Amiens Cathedral exemplify this quality. He also adds and mentions the importance of light in the cathedral, saying that if geometric regularity is a feature of all great churches, what, then, distinguishes Gothic cathedrals from others? The key to answering this question is understanding the central defining element of the Gothic, light.

All of the features we associate with Gothic architecture, pointed arches, flying buttresses, ribbed vaults, soaring ceilings, stained glass windows, pinnacles and turrets, were developed in the service of the desire to flood the interior space with as much as light possible.

|

| The Labyrinth of Amiens Cathedral. |

Unlike Reims Cathedral, Amiens has preserved its labyrinth. A work from the 12th century, it is an octagonal geometric shape engraved across the whole width of the main nave’s pavement, at the fifth bay. The labyrinth appeared to be a symbolic road where man meets God. The centre of this great design would therefore symbolise heavenly Jerusalem or the hereafter. Its path measures 234 metres. The pilgrims who came to venerate the relics of John the Baptist that were brought back in 1206, had the tradition of walking along it on their knees by following the black line.

The central stone of the labyrinth contains an inscription on a copper strip and summarises the groundwork of the cathedral. The stone is actually a copy; the original dating from 1288 is located at the Museum of Picardy. The paving of the nave has a series of designs restored in the 19th century. They include, among others, the swastika pattern.

|

| The Center of the Labyrinth. |

The Sculptural Program of Amiens Cathedral

The sculptural program of the portals of Amiens Cathedral has been construed here within a framework of change. In their material state the stone statues and reliefs of the portals are caught up in the same inexorable process of physical deformation or change that affects our own bodies: progressive decay that will ultimately lead to disappearance.

The current program of conservation, begun in 1992, has drawn attention emphatically toward this accelerating process of decomposition. Yet, paradoxically, these stone figures were intended to be permanent, projecting images of changelessness. The column figures depict human beings who have resisted the corrosion of sin during life, in some cases triumphing over martyrdom, thus becoming the elect who look forward to the perfect state after resurrection.

The paradox can be extended into the very process by which these images of perfection and changelessness were made. This was a process in which change played a considerable initial role. Thus, the early work on the voussoir sculptures of the south portal of the west façade and the first column figures was characterized by experimentation and stylistic pluralism. The architecture of Amiens Cathedral, conversely, began with the exercise of powerfully centralized control over the means of production. This control is palpable in the repeated “unchanging" forms of the nave; identical piers, windows, vaults and flyers.

Whereas the high level of uniformity in the architectural forms of the cathedral was broken by the revolution of the mid-1240s (upper transept and upper choir), in the sculpture initial pluralism was overlaid by the powerful sameness of the column figures, particularly the Apostles and minor prophets (work of the 1230s and 1240s). This emphatic sameness signifies the participation of the elect in the mystical body of Christ which is the Church, providing a glimpse of the perfection of the post-resurrection body.

The Conclusion

Beginning in the eventful year of 1220, Bishop Evrard de Fouilloy initiated the work on a cathedral that would astound and bring awe to all who gazed upon it. Named after the region it was erected in, the Cathédrale Notre Dame d'Amiens is still active to this day. This magnificent cathedral is the tallest complete cathedral in France, and also has the most interior space of any cathedral in France. The cathedral has also been celebrated as a UNESCO World Heritage Site since 1981. Despite losing the majority of its stained glass windows, the Amiens Cathedral is widely awarded because of its 13th century Gothic style and beauty.

Although always acclaimed as a gorgeous and ever successful display of Gothic architecture, there were some drastic defects in the Amiens Cathedral’s original design. The original flying buttresses to provide structural soundness while maintaining beauty, were placed much too high on the cathedral. This led to the ceiling arch putting excess lateral force on the fragile vertical columns. To fix this problem, a second row of more robust buttresses closer to the base of the outer wall was built. This addition fixed the original dilemma, but added new stress on the lower inner wall, and threatening to collapse the magnificent structure. The final correction was made years later when architects added an iron bar chain around the base level of the cathedral. This counteracted the forces the vertical columns were placing on the outer walls, and kept the lower inner walls from collapsing due to stress.

The perfectly exemplified wall features three symmetrical and large arches at the base of the cathedral, the arch in the middle being significantly larger. Above the arches are twenty-two oversized kings, who were carved in great detail, and stretch all the way across the façade. Above the famous kings is the centerpiece of the entire cathedral, the rose window. It is nearly impossibly difficult to describe the eminent glory of the rose window, but it is made up of a large circular pane of glass. Just above the rose window is an open arcade. Both towers are recognized by the trained eye as being artistically dissimilar to the rest of the west face. The western front in itself is one of the most awe inspiring architectural feats ever constructed.

The interior of the Amiens Cathedral is famous for its vast space, which is the largest in medieval Western Europe. The nave and altar area are engulfed in light from the windows, and both are flanked by an array of different chapels.

Overall, the Notre Dame d’Amiens is highly regarded as one of the most beautiful cathedrals in the world. Despite the many difficulties associated with the cathedral, it is still acclaimed and in use today. The glorious western façade, magnificently spacious interior, and mysterious history of the cathedral all add to the splendor and amiability of the famous project.

References

Branner, Robert, "Gothic Architecture". New York: George Braziller, 1967.

Pryce, Will, "World Architecture: The Masterworks". London: Thames Hodson, 2008.

Scott, Robert A., "The Gothic Enterprise". London: University of California Press, 2003.

Wilson, Christopher, "The Gothic Cathedral". New York: Thames Hodson, 2004.

Excelente. Felicitaciones (spanish, español)

YanıtlaSil